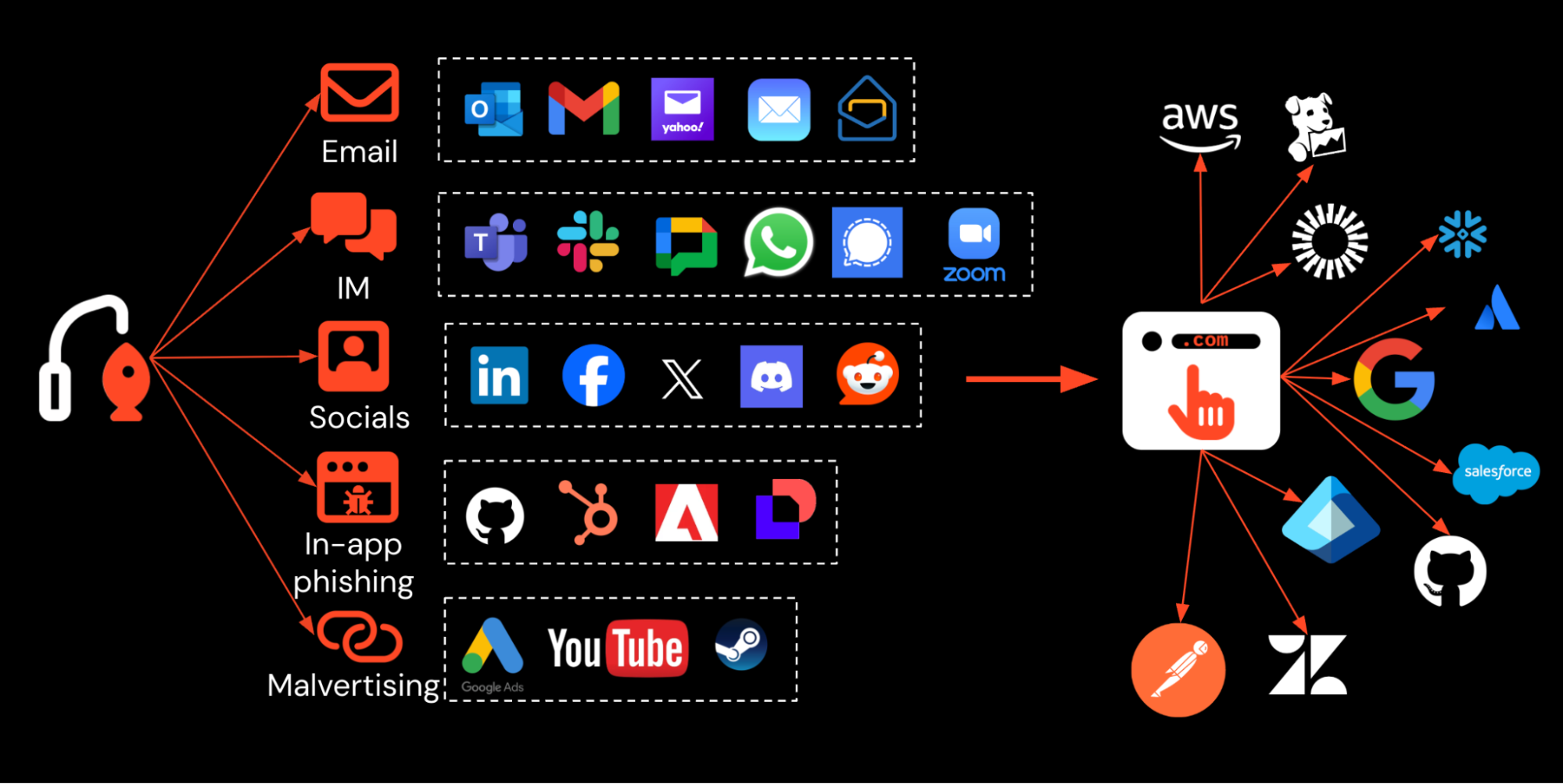

Attackers are increasingly sending phishing links over non-email delivery channels like social media, instant messaging apps, and malicious search engine ads. In this article, we explore why phishing attacks are moving away from exclusively email-based delivery, and what this means for security teams.

Attackers are increasingly sending phishing links over non-email delivery channels like social media, instant messaging apps, and malicious search engine ads. In this article, we explore why phishing attacks are moving away from exclusively email-based delivery, and what this means for security teams.

Phishing has moved outside of the mailbox

Because of the changes to working practices, employees are more accessible than ever to external attackers. Once upon a time, email was the primary communication channel with the wider world, and work happened locally — on your device, and inside your locked-down network environment. This made email and the endpoint the highest priority from a security perspective.

But now, with modern work happening across a network of decentralized internet apps, and more varied communication channels outside of email, it’s harder to stop users from interacting with malicious content.

Attackers can deliver links over instant messenger apps, social media, SMS, malicious ads, and using in-app messenger functionality, as well as sending emails directly from SaaS services to bypass email-based checks. Likewise, there are now hundreds of apps per enterprise to target, with varying levels of account security configuration.

Why am I not hearing about this more?

Phishing attacks outside of email usually go unreported. This is to be expected when most of the industry’s data on phishing attacks comes from email security vendors and tools.

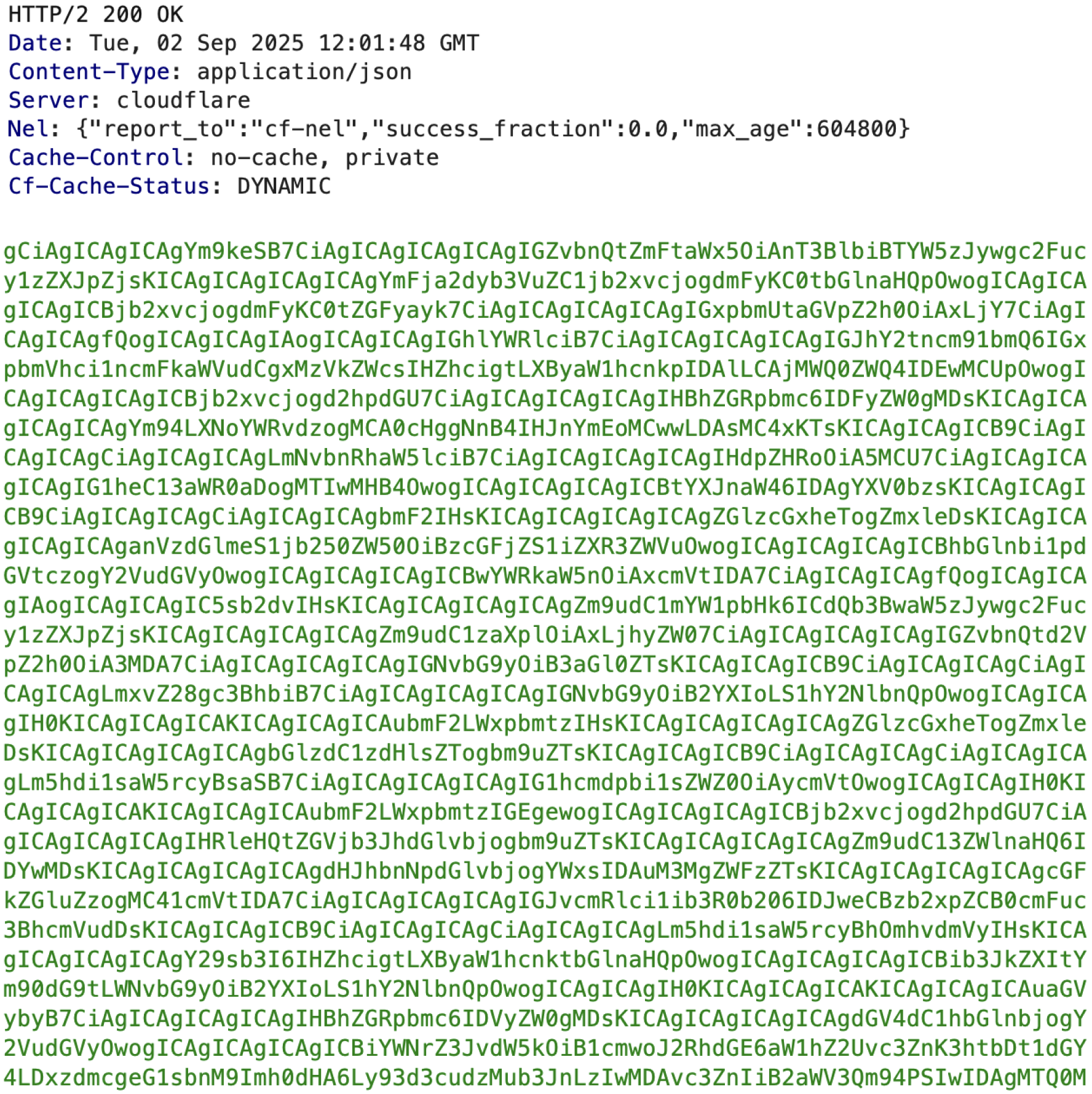

If phishing bypasses the email layer, most organizations are left relying on user reported attacks. Some organizations might supplement this with a web proxy, but these are being increasingly defeated by modern phishing kits, which use an array of obfuscation and detection evasion techniques to bypass these detections.

The most valuable information for security teams today is the webpage that is loaded through the network traffic: What does the HTML body look like? What is the user likely seeing on the page? To do this, you need to stitch together and reconstruct what the browser is doing by looking at the network data. Except for very simple websites, this happens through JavaScript on the client side.

This is hard enough when analysing a typical SaaS app. But the latest generation of fully customized Attacker-in-the-Middle (AitM) phishing kits are going out of their way to make this as challenging as possible, using techniques like DOM obfuscation, Page obfuscation, and Code obfuscation so all you see at a network layer is a garbled, obfuscated mess of JS code.

So, non-email phishing is going broadly undetected through technical controls. And even when spotted and reported by a user — what can you really do about it?

Take a social media phish. You can’t see which other accounts were targeted or hit in your user base. Unlike email, there’s no way to recall or quarantine the same message hitting multiple users. There’s no rule you can modify, or senders you can block. You can report the account, and maybe something will happen when the site owner gets around to it — but the attacker has probably got what they needed by then and moved on.

Most organizations simply block the URLs involved. But this doesn’t really help when attackers are rapidly rotating their phishing domains — by the time you block one site, another three have already taken its place.

But aren’t these just personal accounts?

Modern phishing attacks blur the boundary between corporate and personal. The fact is that your employees are routinely accessing personal messaging and social media apps on their corporate devices. Users are signed into apps like LinkedIn, X, WhatsApp, Signal, even message boards like Reddit on their work laptop and/or mobile devices. And with malicious links being found on search engines (aka. malvertising), they can even stumble upon them while browsing the web normally.

In short: anywhere that your users can be contacted by someone outside of your organization presents an opportunity for phishing. In fact, in most of these cases people expect to be contacted by people they don’t know.

It’s also a myth that campaigns can’t be targeted in the same way on these platforms, that they’re somehow more random and therefore less dangerous. For example, social media accounts are some of the easiest for attackers to create en masse — or take over. According to the most recent Verizon DBIR, 60%+ of creds found in infostealer logs were from social media sites. They’re also likely to use single-factor logins. If an attacker can take over one account, and use it to credibly communicate with one of your employees, they have a way higher likelihood of being successful than with your average unsolicited email.

Malicious ads can also be targeted. For example, Google Ads can be targeted to searches coming from specific geographic locations, tailored to specific email domain matches, or specific device types (e.g. desktop, mobile, etc.). If you know where your target organization is located, you can tailor the ad to that location. Phishing sites also often come with conditional loading parameters to only deliver the malicious payload under specific conditions — for example, only if the visitor came from a particular email campaign link, or only if they are in a certain organization, using a certain browser, from a specific IP range, etc.

And even if the attacker only manages to reach your employee on their personal device, this can still be laundered into a corporate account compromise. Just look at the 2023 Okta breach, where an attacker exploited the fact that an Okta employee had signed into a personal Google profile on their work device. This meant any credentials saved in their browser were synced to their personal device — including a customer support system service account providing access to 134 customer tenants. When their personal device got hacked, so too did all of their work credentials.

So, there’s plenty of scope for non-email phishing to result in targeted phishing campaigns. If anything, it’s arguably less work for the attacker to spin up these non-email campaigns than it is to do the necessary legwork to create and build up email sender reputation!

Case study: LinkedIn spear-phishing

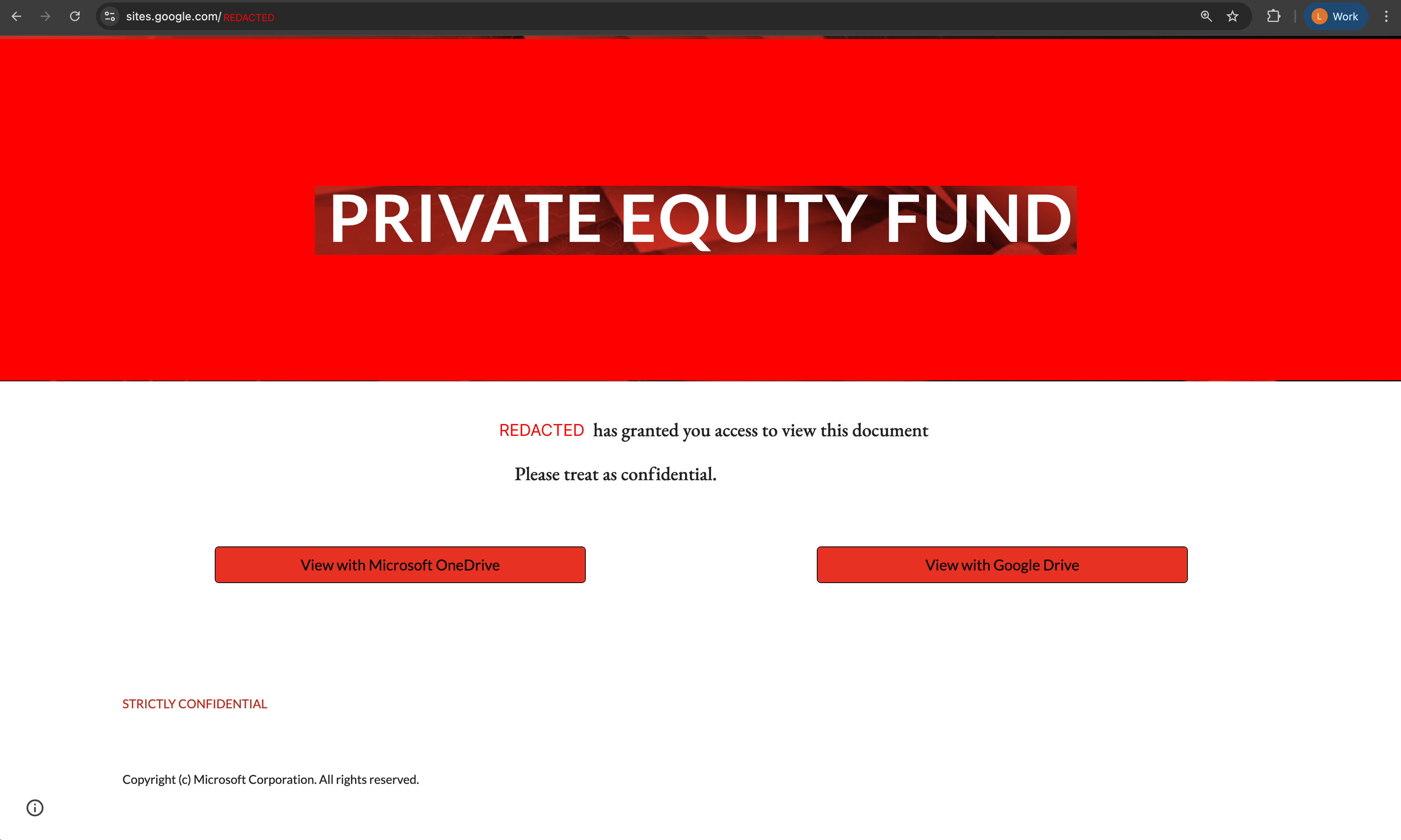

Attackers recently ran a LinkedIn spear-phishing campaign targeting tech company execs. The victims were targeted via LinkedIn direct message from another exec about a fake investment opportunity. The sender’s account had been compromised and used to approach high-value targets.

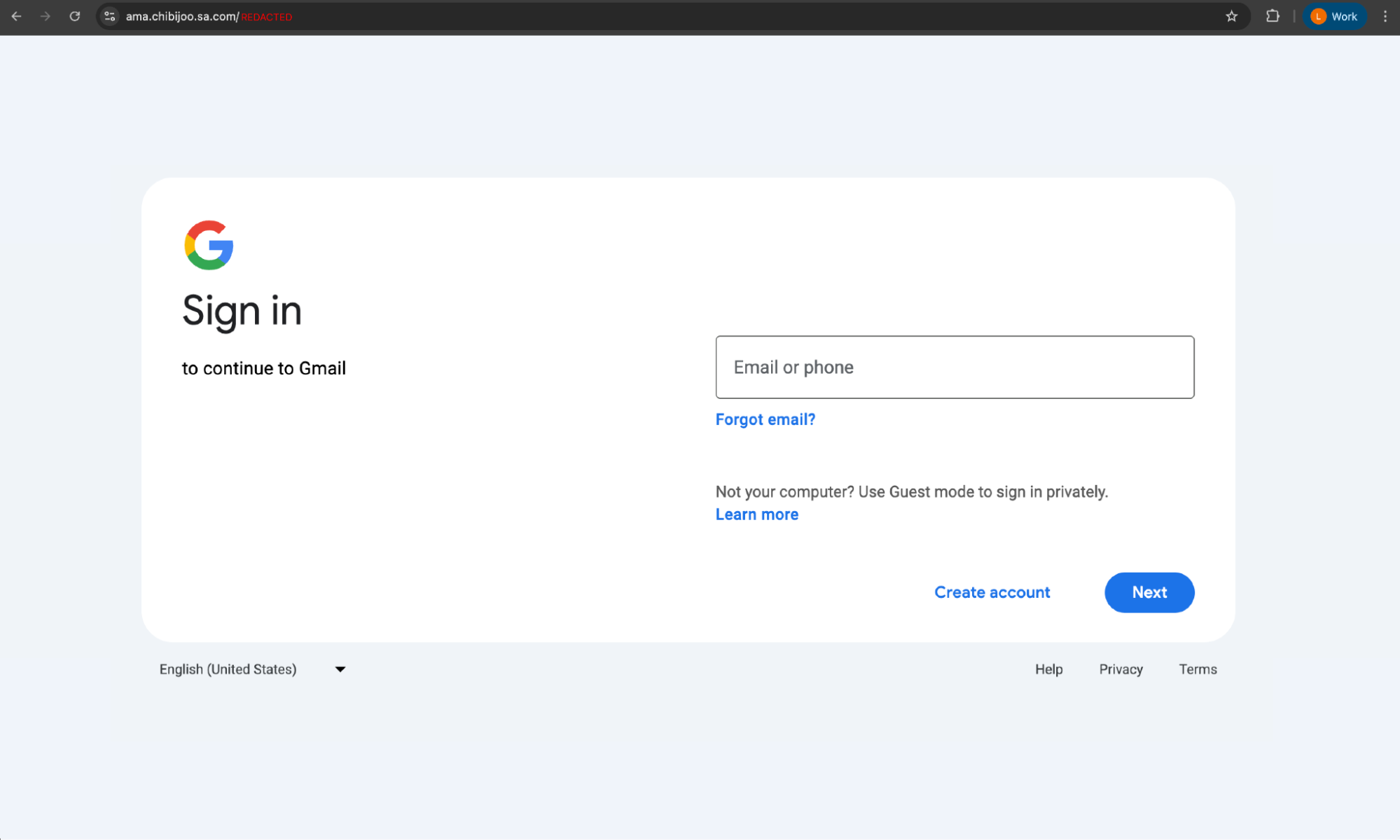

The attack led the victim through a chain of custom pages hosted on legitimate sites (a well-known detection evasion technique) such as Google Sites, Google Search, and Microsoft Dynamics, before serving up an Attacker-in-the-Middle phishing page impersonating Google Workspace, before serving up a session-stealing AitM phishing page.

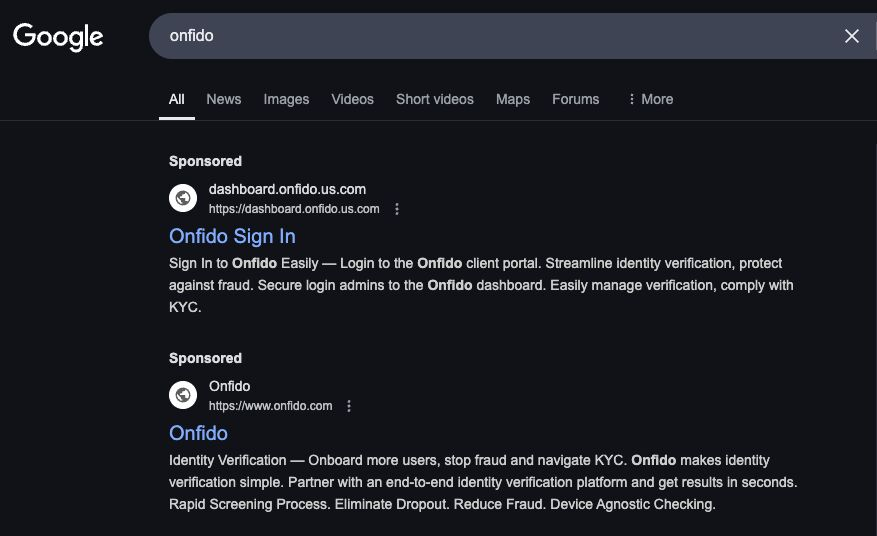

Case study: Google Search malvertising

A company was hit with a targeted Google ad which was designed to look highly convincing, and positioned above the legitimate ad. This took advantage of the fact that many users will search for login pages rather than accessing the site via bookmark.

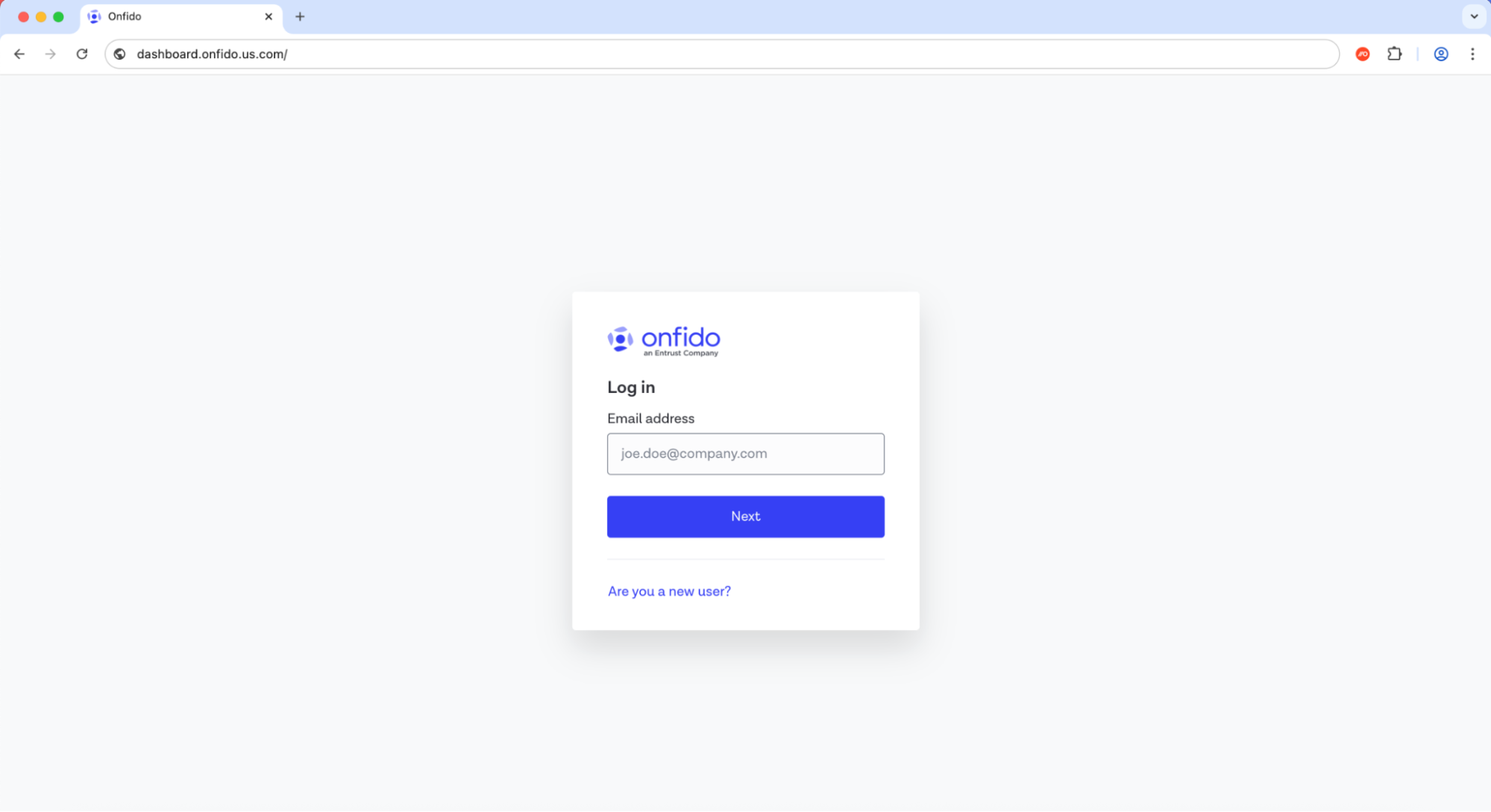

In this case, the attacker had made use of a rentable subdomain (us[.]com) to make the link appear highly legitimate, with only small changes to the real URL that were easy to miss.

Instead of the real login, the link took the victim to a session-stealing AITM page.

This was later traced back to a Scattered Spider campaign.

What can an attacker do with a compromised account?

It’s important to think about the bigger picture when it comes to a modern phishing compromise.

Most phishing attacks focus on core enterprise cloud platforms such as Microsoft and Google, or specialist Identity Providers like Okta. Taking over one of these accounts doesn’t just give access to the core apps and data within the respective app, but also enables the attacker to leverage SSO to sign into any connected app that the employee logs into with their account.

This gives an attacker access to just about every core business function and dataset in your organization. And from this point, it’s much easier to target other users of these internal apps — using internal messenger apps like Slack or Teams, or techniques like SAMLjacking to turn an app into a watering hole for other users trying to log in.

A single account compromise can quickly snowball into a multi-million dollar, business-wide breach.

What can organizations do about non-email phishing?

It’s clear that the traditional anti-phishing toolset hasn’t kept up with phishing innovation.

To tackle modern phishing attacks, organizations need a solution that detects and blocks phishing across all apps and delivery vectors.

Push Security doesn’t detect the redirect tricks, or rely on outdated domain TI feeds. It doesn’t matter what delivery channel or camouflage methods are used, Push detects and blocks attacks by identifying the attack in real time, as the user loads and interacts with the page in their web browser.

Push’s browser-based security platform provides comprehensive identity attack detection and response capabilities against techniques like AiTM phishing, credential stuffing, ClickFixing, malicious browser extensions, and session hijacking using stolen session tokens.

To learn more about Push, check out our latest product overview or book some time with one of our team for a live demo.