We recently intercepted a phishing campaign using a new kind of attack technique that we’re calling “ConsentFix” — combining OAuth consent phishing with a ClickFix-style user prompt that leads to account compromise. Here's what you need to know.

We recently intercepted a phishing campaign using a new kind of attack technique that we’re calling “ConsentFix” — combining OAuth consent phishing with a ClickFix-style user prompt that leads to account compromise. Here's what you need to know.

Introducing “ConsentFix” — a new kind of phishing attack

The Push browser agent recently detected and blocked a new attack technique seen targeting several Push customers.

This is a new kind of browser-based attack technique that takes over user accounts with a simple copy and paste. If you’re already logged into the app in your browser, you don’t even need to supply creds, or pass an MFA check — meaning it effectively circumvents phishing-resistant auth like passkeys too.

This is so different from the AiTM phish kits we usually come up against that we felt it deserved a new name.

Enter: ConsentFix. This attack shares a lot of similarities with ClickFix/FileFix, AiTM phishing, and OAuth Consent Phishing. You can think of this as a browser-native ClickFix attack that phishes an OAuth token on a target app by getting the victim to copy and paste a URL containing OAuth key material into a phishing page.

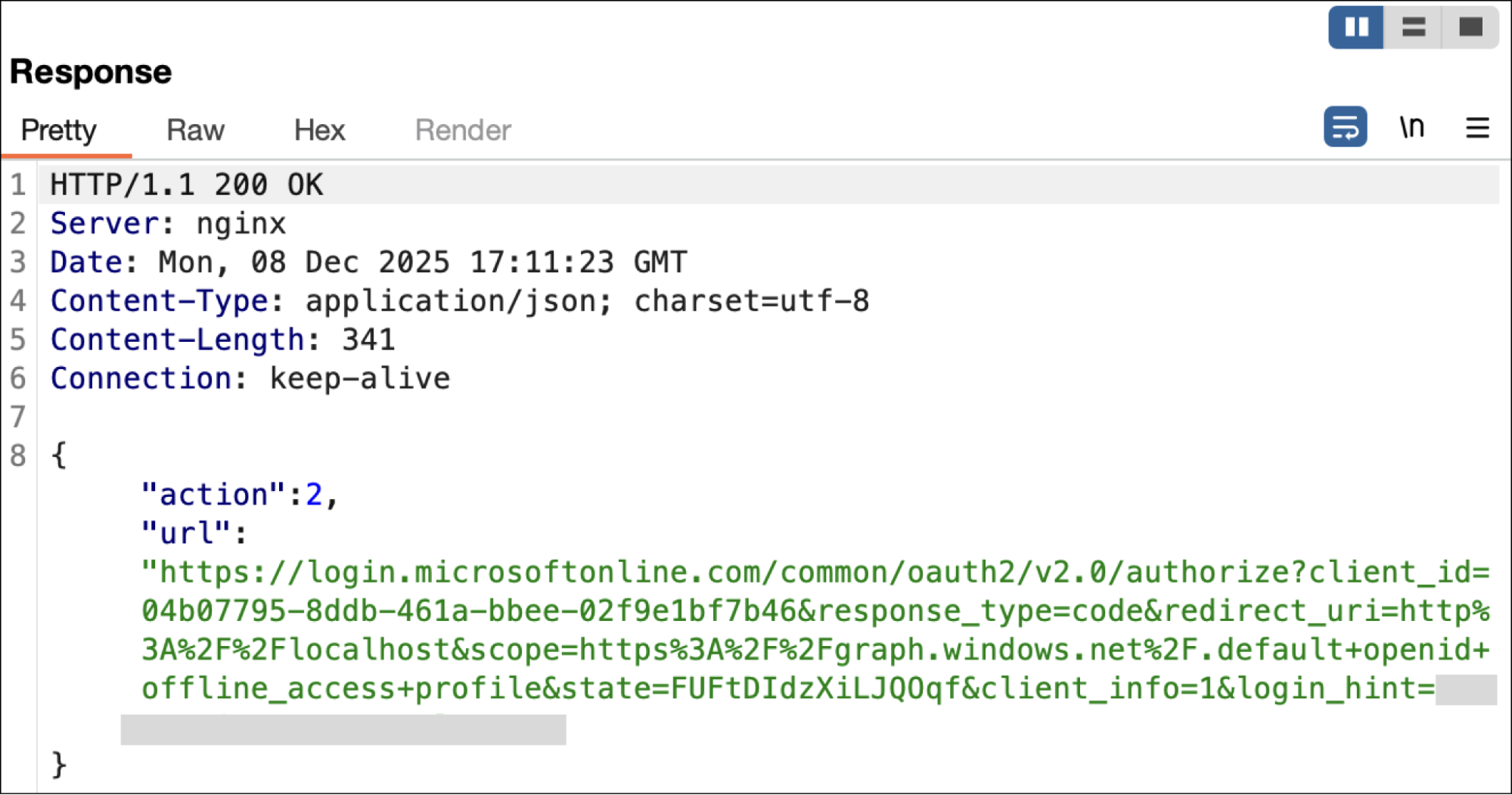

The campaign we detected looks to be specifically targeting Microsoft accounts by abusing the Azure CLI OAuth app. Essentially, the attacker tricks the victim into logging into Azure CLI, by generating an OAuth authorization code — visible in a localhost URL — and then pasting that URL (including the code) into an attacker-controlled page. This then creates an OAuth connection between the victim’s Microsoft account and the attacker’s Azure CLI instance.

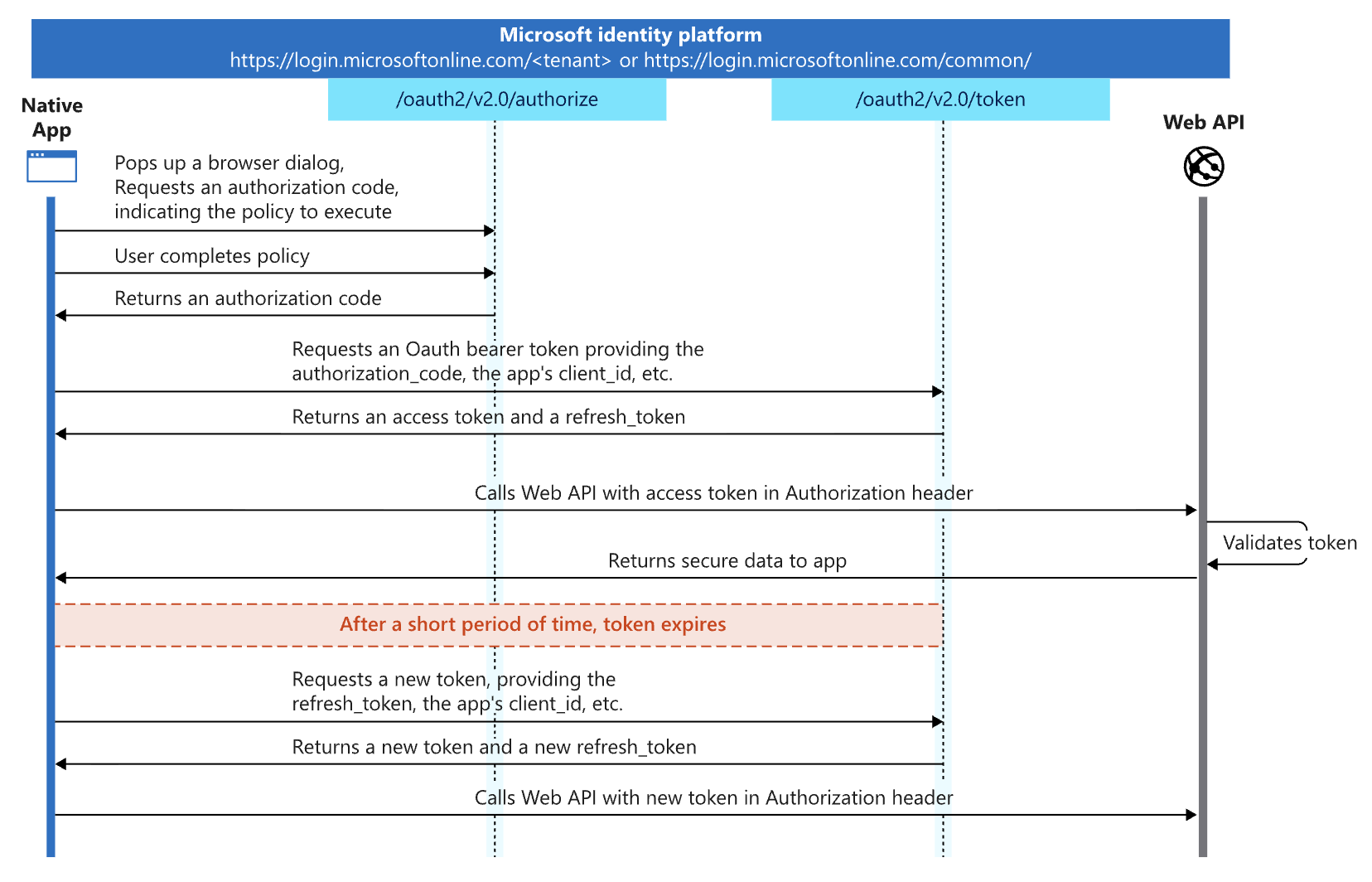

Authorization code flow is an OAuth 2.0 protocol for web applications to get a user's permission to access protected resources. When using the authorization code flow to connect an app, it combines the code with an OAuth secret held by the app in exchange for a token (the valuable part). However, some apps can’t protect a secret — for example, apps that run on your mobile device or desktop. In this case, the code alone is enough to generate an OAuth token, without the secret — which is what is being exploited here.

How ConsentFix works

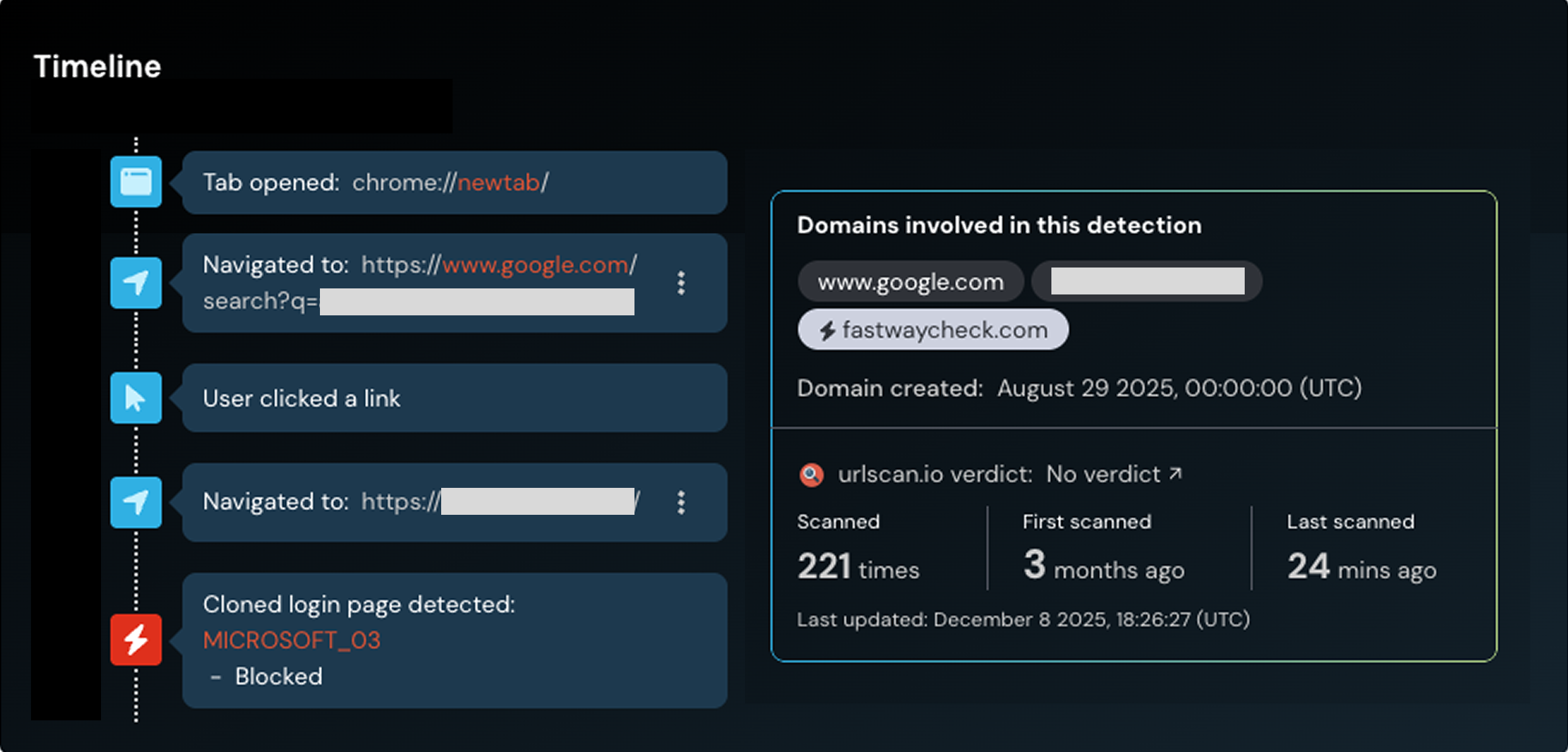

In all of the examples we saw, the victim accessed a malicious or compromised webpage via Google Search. The vast majority of the sites we’ve seen associated with the campaign are legitimate, compromised websites with high domain reputation that are easily findable via search engines.

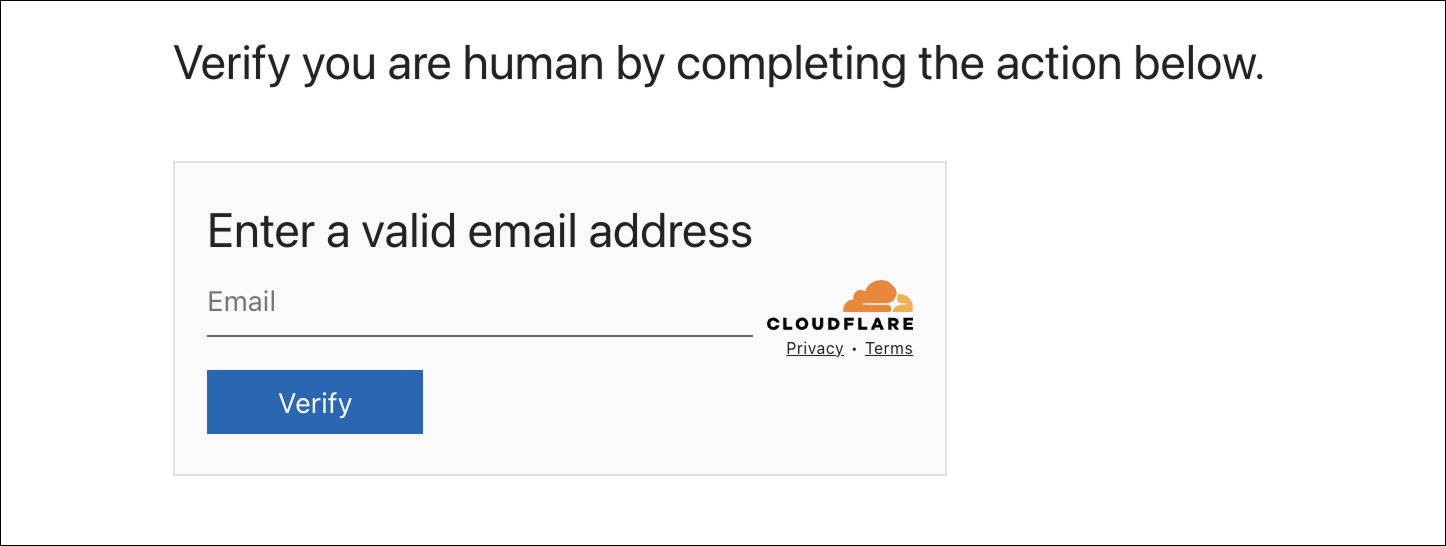

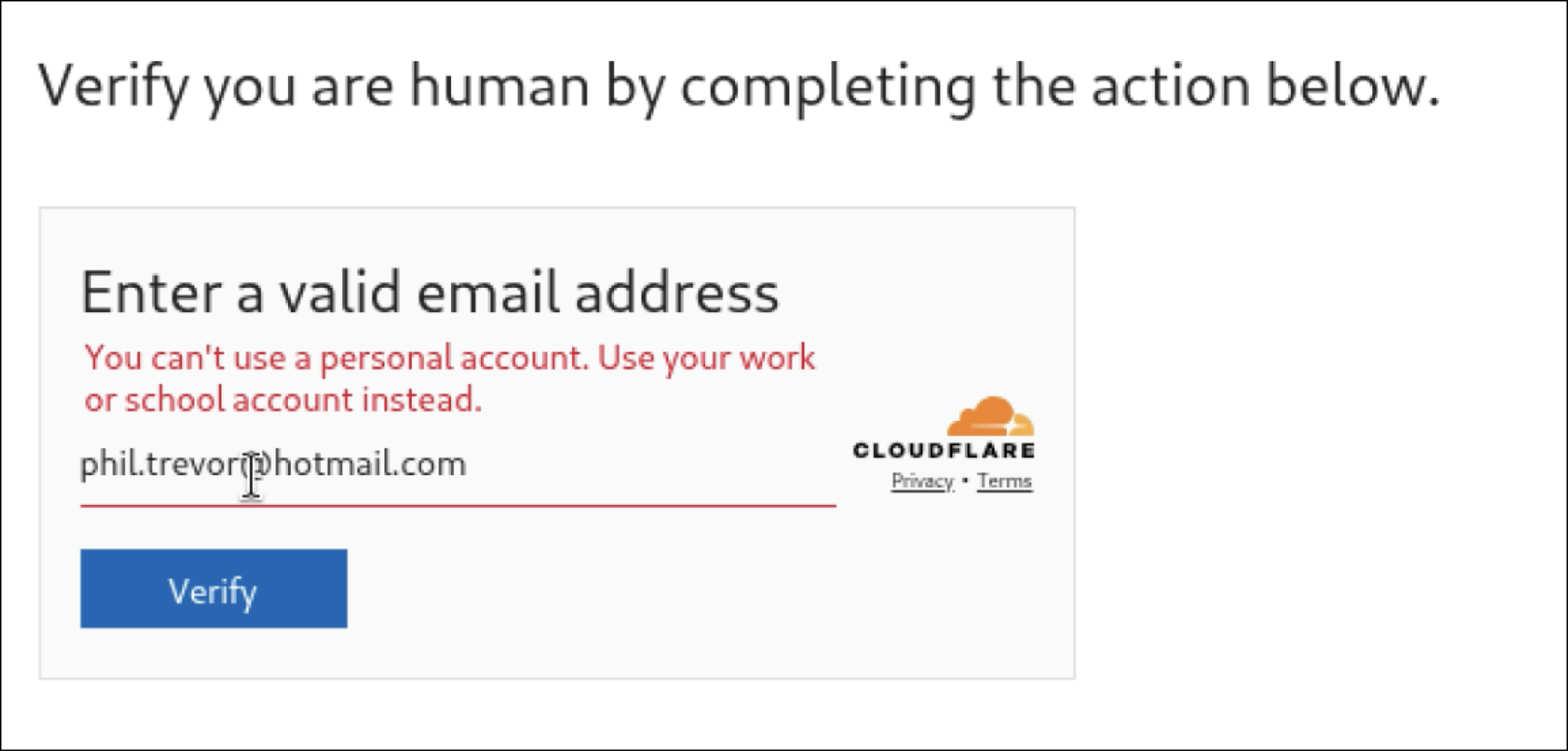

The attacker had injected a fake Cloudflare Turnstile into the compromised websites, requiring an email address to be supplied in order to proceed.

This acted as a form of conditional loading that would only continue if a valid email address and domain was supplied, designed to prevent the page from being analysed by security bots, analysts, and low-value accounts that run the risk of exposing the campaign before the intended recipient(s) can be phished.

If a domain not on the target list was provided, the victim was passed back to the original website and the attack did not progress to the next stage. Further, once the check has concluded per IP, the phishing page will no longer activate, even a different email is provided.

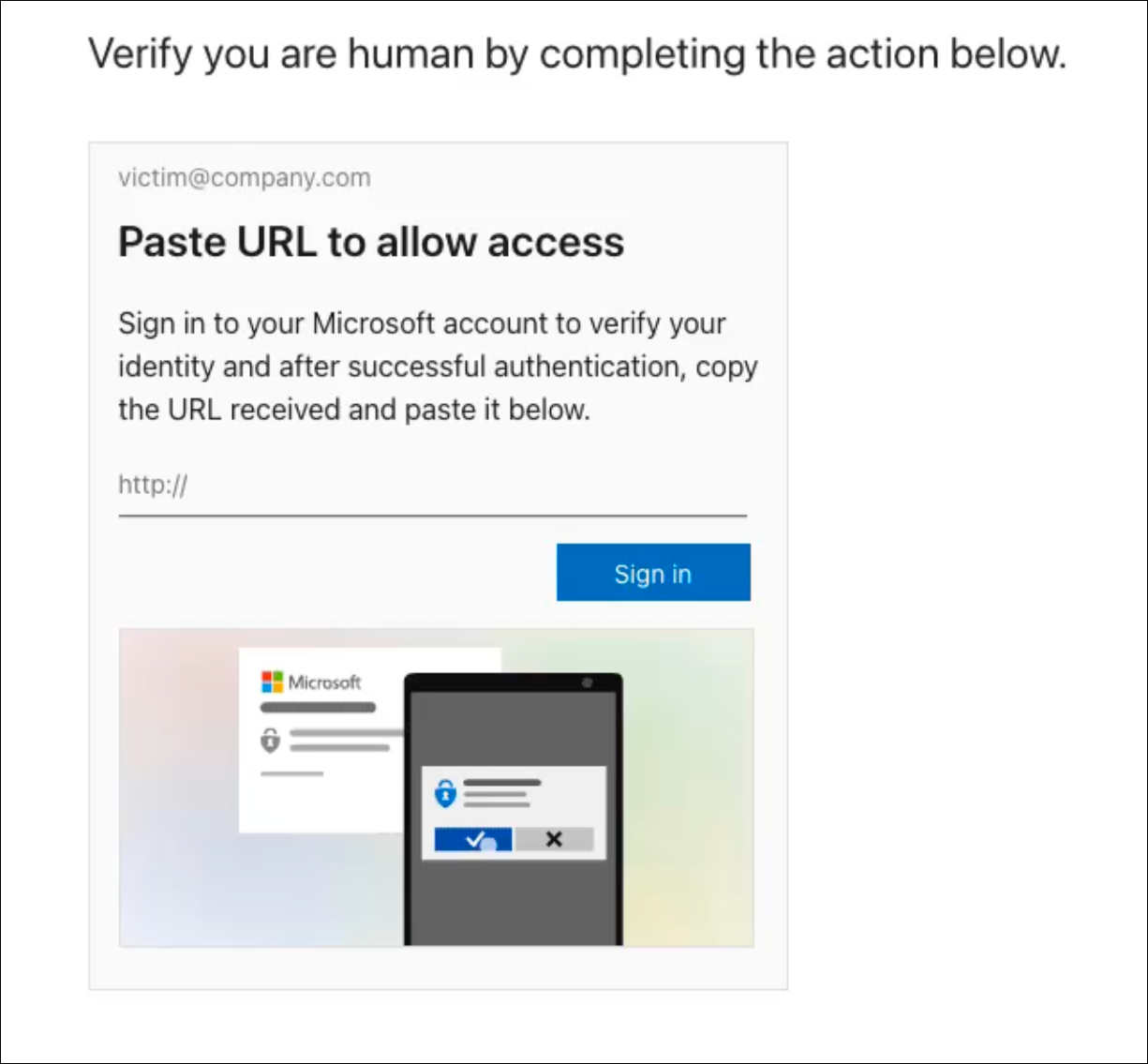

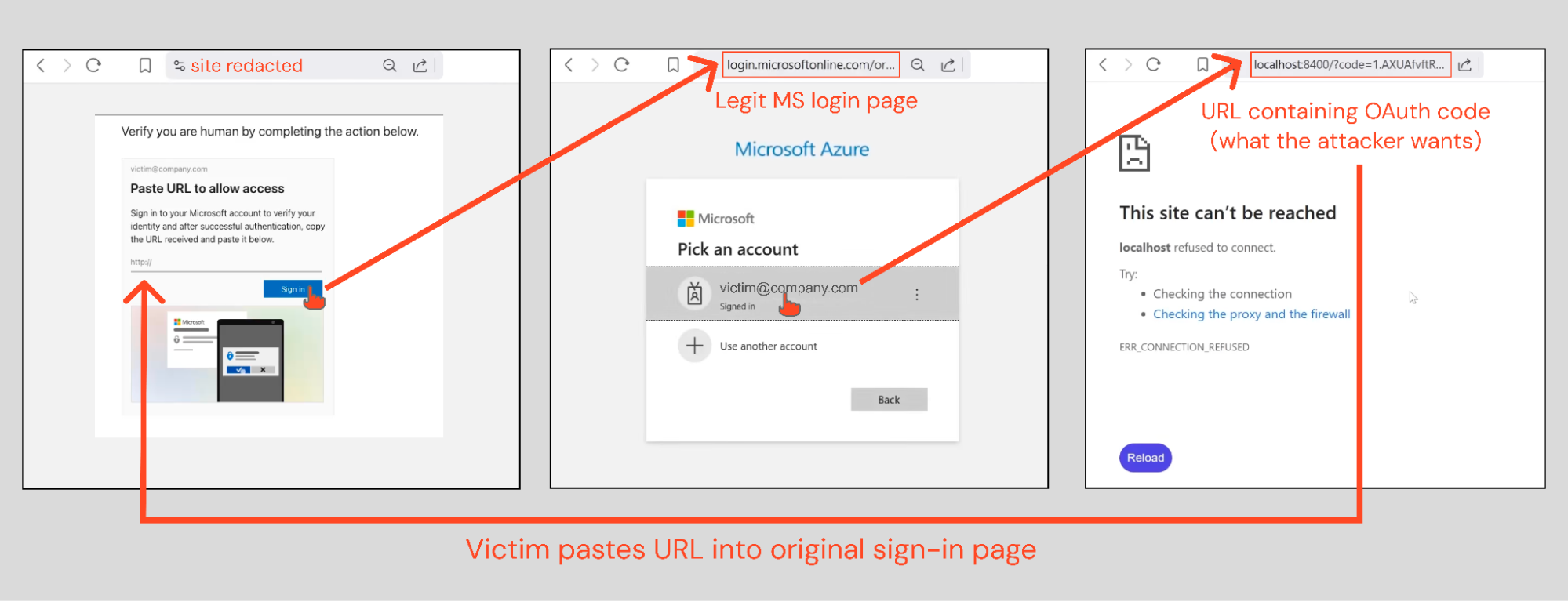

After entering an approved email address, the next stage was loaded, prompting the victim to complete a set of instructions on the page to continue.

To complete the attack, the victim must:

Click the “Sign In” button. This opens a new tab that loads a legitimate Microsoft URL associated with the user account/email used to access the page.

If the user is already logged into Microsoft in their browser, they simply need to select their MS account from the dropdown. Otherwise, they will be required to login via the legitimate Microsoft login URL (no phishing takes place at this stage).

Once logged into legit Microsoft or the account is selected from the dropdown, the user is redirected to localhost, which generates a URL containing a code associated with the user’s Microsoft account.

To complete the phish, the victim copies the URL and pastes it onto the original page.

Once the steps are completed, the victim has granted the attacker access to their Microsoft account via Azure CLI.

At this point, the attacker has effective control of the victim’s Microsoft account, but without ever needing to phish a password, or pass an MFA check. In fact, if the user was already logged in to their Microsoft account (i.e. they had an active session) no login is required at all.

The next evolution of ClickFix?

When we presented our last webinar on ClickFix, we predicted that the next evolution of the attack would happen entirely within the browser context. This is because any attack that touches the endpoint (a traditionally much better protected surface) is way more likely to be detected. And with many ClickFix attacks being used to deliver infostealer malware, these attacks are really trying to get back into the browser anyway — to steal credentials and sessions stored there.

Let’s take a closer look at the page — if you follow Push research, you might be getting déjà vu.

We’ve seen this kind of embedded video player before (albeit a slicker looking one) that we blogged about as the most advanced ClickFix we’d seen.

Another similarity with ClickFix campaigns we’ve investigated is the use of Google Search as a delivery vector. 4 in 5 ClickFix attacks intercepted by Push came via Google Search, with attackers using malvertising and either compromised or custom vibe-coded websites to intercept users as they browse the internet.

So it seems highly likely that this is a kind of browser-native evolution of ClickFix that shares many elements with typical ClickFix attacks, and is probably used by the same groups of attackers.

OAuth shenanigans via Azure CLI

The clever use of Azure CLI and OAuth consent abuse is another clever iteration on previous techniques.

We’ve previously seen consent phishing and device code phishing attacks where attackers have tricked victims into connecting malicious external apps into their tenant via OAuth, but this is becoming increasingly difficult in core enterprise cloud environments like Azure due to stricter default configs. However, since Azure CLI is a first-party Microsoft app, it is implicitly trusted in Entra ID, and is excluded from these restrictions.

First-party apps like Azure CLI are trusted by default in all tenants, allowed to request permissions without admin approval, and cannot be deleted or blocked. They can also be granted special permissions, such as tenant-wide service permissions (without needing admin approval), use of legacy or undocumented graph scopes, internal scopes for Microsoft client operations, and permissions for Office/Entra admin functions. This makes Azure CLI a prime target for attackers, and significantly more exploitable than when connecting a third-party app.

Advanced detection evasion techniques

This campaign features some of the most advanced detection evasion techniques we've seen in the wild.

As well as the use of Google Search to deliver the lure, and bot protection to prevent security tools from analysing the page, there were multiple layers of anti-analysis techniques to navigate.

We already mentioned the use of selective targeting based on email addresses and domain names. But all sites involved in the campaign also have synchronized IP blocking — meaning if you visit one site and are served one of the associated phishing pages, the phish will never be served again, across any of the sites linked to the campaign. When you visit any of the sites again, the phish won't trigger, and it can be browsed as normal.

On the backend, there are multiple checks based on your IP and identifiers unique to your session. Unless all of the conditions are met, certain JavaScript packages won't be served — preventing full inspection of the page to detect malicious elements.

If the conditions aren't met, the page may not load the Cloudflare Turnstile check at all, or will redirect you back to the site to continue browsing as normal.

All of these make it incredibly hard to detect and block these attacks ahead of time when relying on URL-based checks and traffic analysis.

Key takeaways

ConsentFix is a dangerous evolution of ClickFix and consent phishing that is incredibly hard for traditional security tools to detect and block, as:

The attack happens entirely inside the browser context, removing one of the key detection opportunities for ClickFix (because it doesn’t touch the endpoint).

Delivering the lure via a Google Search watering hole attack completely circumvents email-based anti-phishing controls.

Targeting a first-party app like Azure CLI means that many of the mitigating controls available for third-party app integrations do not apply — making this attack way harder to prevent.

Because there’s no login required, phishing-resistant authentication controls like passkeys have no impact on this attack.

The use of advanced detection evasion techniques makes this attack difficult to investigate, meaning these attacks are going undetected.

We’re sure to see more examples of ConsentFix in future. We’ll be monitoring to see how attackers adapt in terms of integrating these capabilities with common as-a-Service offerings to make them more widespread, and whether the scope extends further beyond Microsoft / Azure CLI targets in the future to target other enterprise cloud ecosystems.

Recommendations

Since releasing this research, the security community has jumped on ConsentFix, discovering several additional vulnerable Microsoft apps, and sharing a variety of Microsoft-specific mitigation and detection guidance. You can find this information aggregated in our follow-up blog post here.

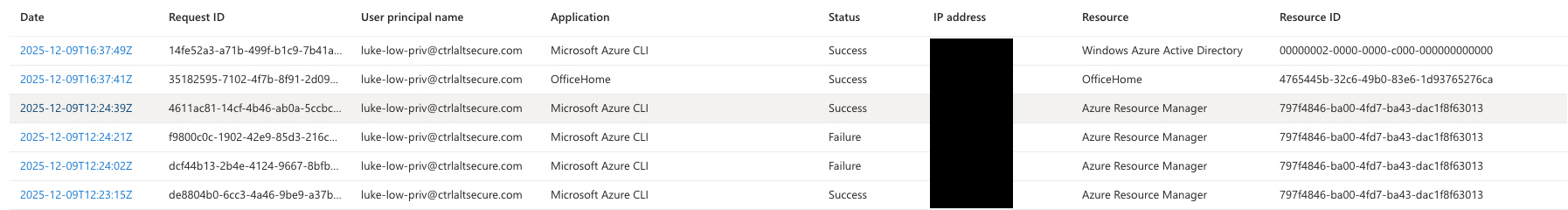

On the backend, exploitation of this attack will lead to login events being observed to the Microsoft Azure CLI app. It’s likely that any legitimate use of this will most likely be limited to system administrators and possibly developers. Therefore, logins outside of these groups will be inherently more suspicious.

Additionally, it’s possible that aspects of the logins themselves will be different between legitimate Azure CLI use and exploitation of this attack. For example, see the following logs from a lab environment. The login events with an application of “Microsoft Azure CLI” and a resource of “Azure Resource Manager” was legitimate use of the Azure CLI using the powershell CLI framework. Conversely, the login event with the Resource of “Windows Azure Active Directory” was produced by logging in using the method used by the phishing kit.

There is no guarantee this can be used to differentiate between legitimate and malicious examples, but it’s another data point to consider. If searching logs you may wish to use the respective GUIDs for these:

Application ID = 04b07795-8ddb-461a-bbee-02f9e1bf7b46

Resource ID = 00000002-0000-0000-c000-000000000000

For interactive logins, like above, you cannot rely on looking for logins from suspicious IP addresses or locations. The login itself occurs from the victims browser directly to Microsoft, and so the IP addresses associated with these events will be the legitimate IP used by the target user, not by the threat actor.

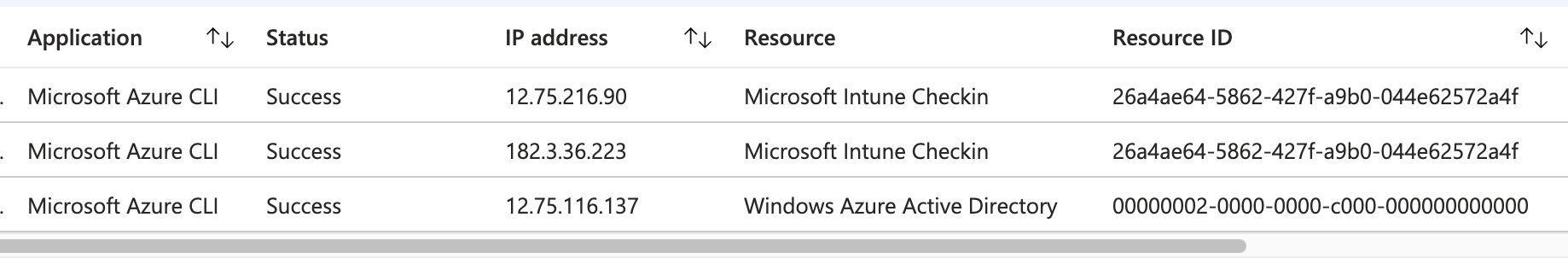

However, for non-interactive logins and other audit logs for actions taken, you may be able to uncover unusual IP addresses that differ from the original interactive login. For example, here are some non-interactive logins that were observed immediately after compromise that came from different IP addresses in both the US and Indonesia.

Interestingly, they differ in which resources they accessed, with one accessing the Windows Azure Active Directory resource ID like the interactive login, but two others accessing the Microsoft Intune Checkin resource ID.

Note: The attacker is intentionally leveraging legacy scopes to evade detection. You should ensure that AADGraphActivityLogs is enabled and monitored to be able to search for unusual activity such as AD enumeration.

IoCs

Short-lived IoCs are of limited value when tackling modern phishing attacks due to the rate at which attackers are able to quickly spin up and rotate the sites used in the attack chain, often dynamically serving different URLs to site visitors.

That said, the domains used to deliver the final phishing payload were:

hxxps://trustpointassurance.com/

hxxps://fastwaycheck.com/

hxxps://previewcentral.com

In addition, we recommend hunting for connections from the following IPs in Azure logs:

12.75.216.90

182.3.36.223

12.75.116.137

How Push stopped the attack

Even though this was a brand new technique, Push intercepted this attack and shut it down before customers could interact with it.

Push doesn’t detect the redirect tricks or rely on outdated domain TI feeds. The reason we detect these attacks (which make it through all the other layers of phishing protection) is that Push sees what your users see. It doesn’t matter what delivery channel or camouflage methods are used, Push shuts the attack down in real time, as the user loads the malicious page in their web browser.

This isn’t all we do: Push’s browser-based security platform provides comprehensive detection and response capabilities against the leading cause of breaches. Push blocks browser-based attacks like AiTM phishing, credential stuffing, malicious browser extensions, ClickFix, and session hijacking. You don’t need to wait until it all goes wrong — you can also use Push to proactively find and fix vulnerabilities across the apps that your employees use, like ghost logins, SSO coverage gaps, MFA gaps, vulnerable passwords, and more to harden your identity attack surface.

To learn more about Push, check out our latest product overview or book some time with one of our team for a live demo.