We recently identified a novel phishing attack combining the latest phishing detection evasion techniques — including clever use of Active Directory Federation Services to get Microsoft to send victims to a phishing site using legitimate login URLs.

We recently identified a novel phishing attack combining the latest phishing detection evasion techniques — including clever use of Active Directory Federation Services to get Microsoft to send victims to a phishing site using legitimate login URLs.

Everything we do at Push is research-driven. Our detections for phishing attacks were created through hands-on analysis of phishing kits that our customers have been targeted with. This gives us a steady supply of all manner of modern Attacker-in-the-Middle phishing kits to analyze — from the classic Evilginx-style phish kit to professionalized criminal as-a-Service infrastructure.

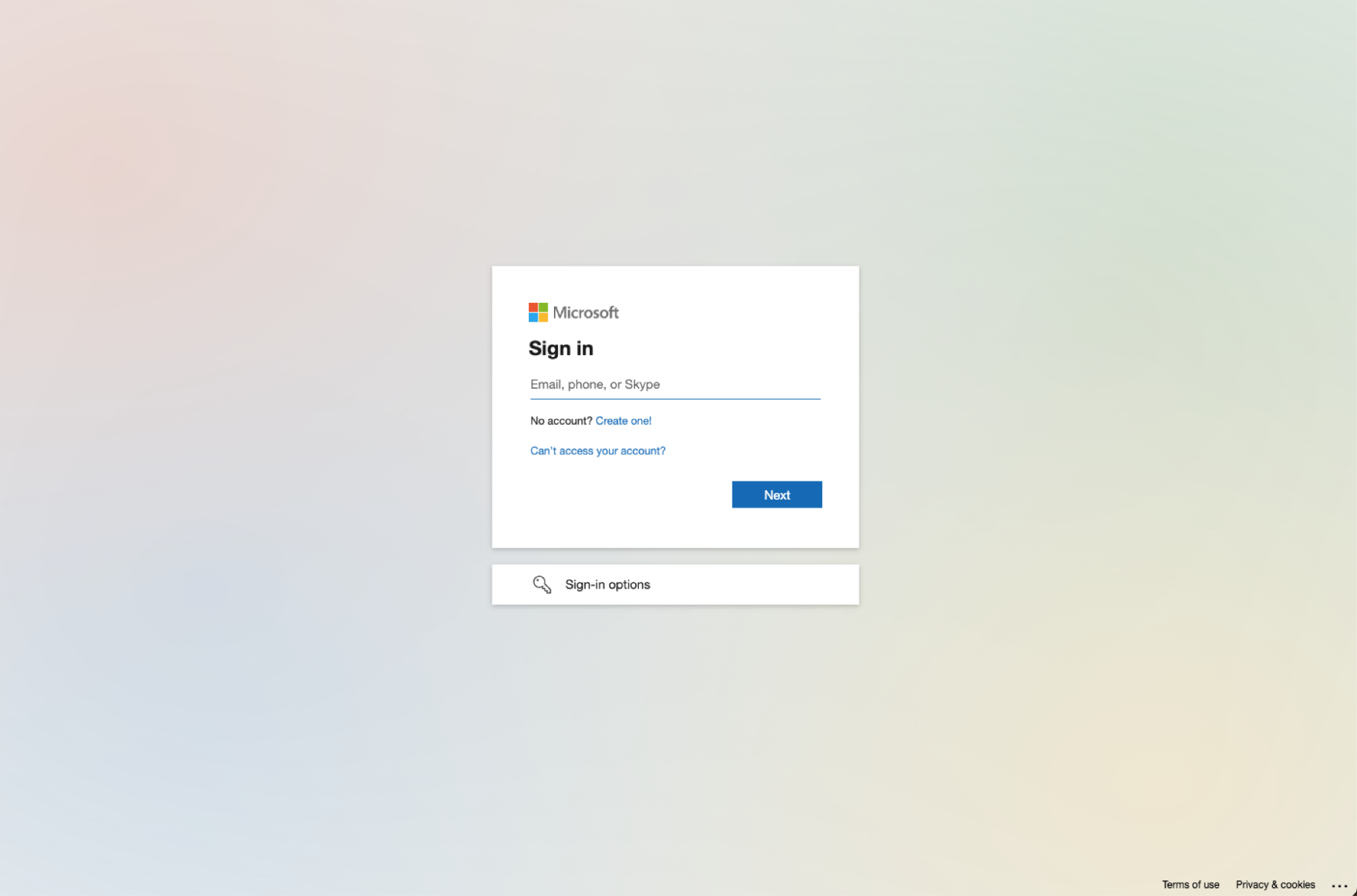

In our most recent phish kit teardown, we encountered a standard reverse-proxy clone of a Microsoft login page — nothing unusual at first glance. But increasingly, a lot of the innovation comes outside of the phishing page itself.

The art in detection evasion comes from being able to successfully deliver the page to a user and have them open the page without it being intercepted by an email security, proxy scanner, URL TI feed, or web analysis tool. To achieve this, the attacker found a way to redirect from a legitimate outlook.office.com link to a phishing website.

This is essentially an open redirect vulnerability — maybe not the classic example where someone has forgotten to do input sanitization on their website, but the outcome is the same.

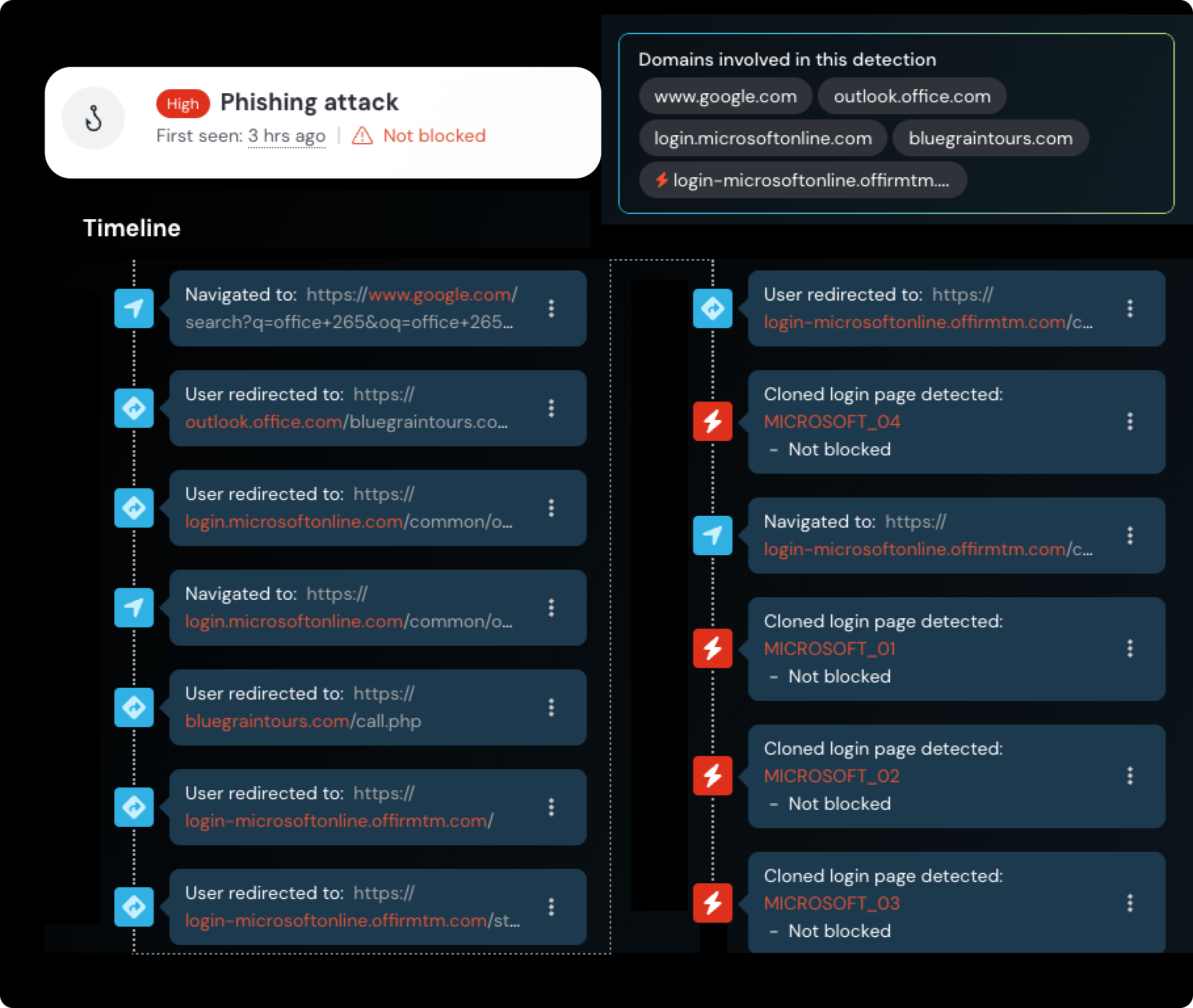

Central to our analysis was the use of our timelines feature, part of our latest Detections feature release. I’m not going to talk in any detail about this, but the TL;DR is that it allows us to trace back the entire chain of browsing activity leading up to a detection — showing the full (sometimes lengthy) redirect chain from the initial link delivery source to the actual phishing page, tabs opened and closed, popup windows, forms submitted, passwords entered, and more.

First, let’s go through the steps of my investigation before looking at the findings (and the implications for phishing detection evasion techniques).

Investigation walkthrough

As I opened with, there was nothing especially notable about the phishing page itself — a standard reverse-proxy AitM page designed to intercept the user’s session as they authenticate, bypassing MFA in the process.

This was not targeted delivery — employees from several customers were impacted. I’ve included an example of how one user arrived at the site below.

This one stood out to me for a few reasons.

The user had accessed the malicious link from Google search. They searched “Office 265" (a typo presumably), clicked a link, and were taken to an Office login page.

The Outlook link had a number of Google Ads tracking parameters attached, meaning they clicked an ad, not an organic link — making this a malvertising attack.

Another domain — bluegraintours[.]com — was in the URL path, after which they were redirected to the Microsoft-impersonating phishing site (login-microsoftonline[.]offirmtm[.]com ...).

This got me wondering — how did they get office.com to redirect to the phishing site, and why was the bluegraintours domain in the path of an office.com link? There was no indication that an actual phishing email was interacted with, it seemed to all happen directly from the legitimate office.com link.

Redirecting to a malicious login page via ADFS

From memory, I knew that the tenant name can appear in the URL when you’re accessing a specific Microsoft tenant for your organization — essentially a domain-specific landing page.

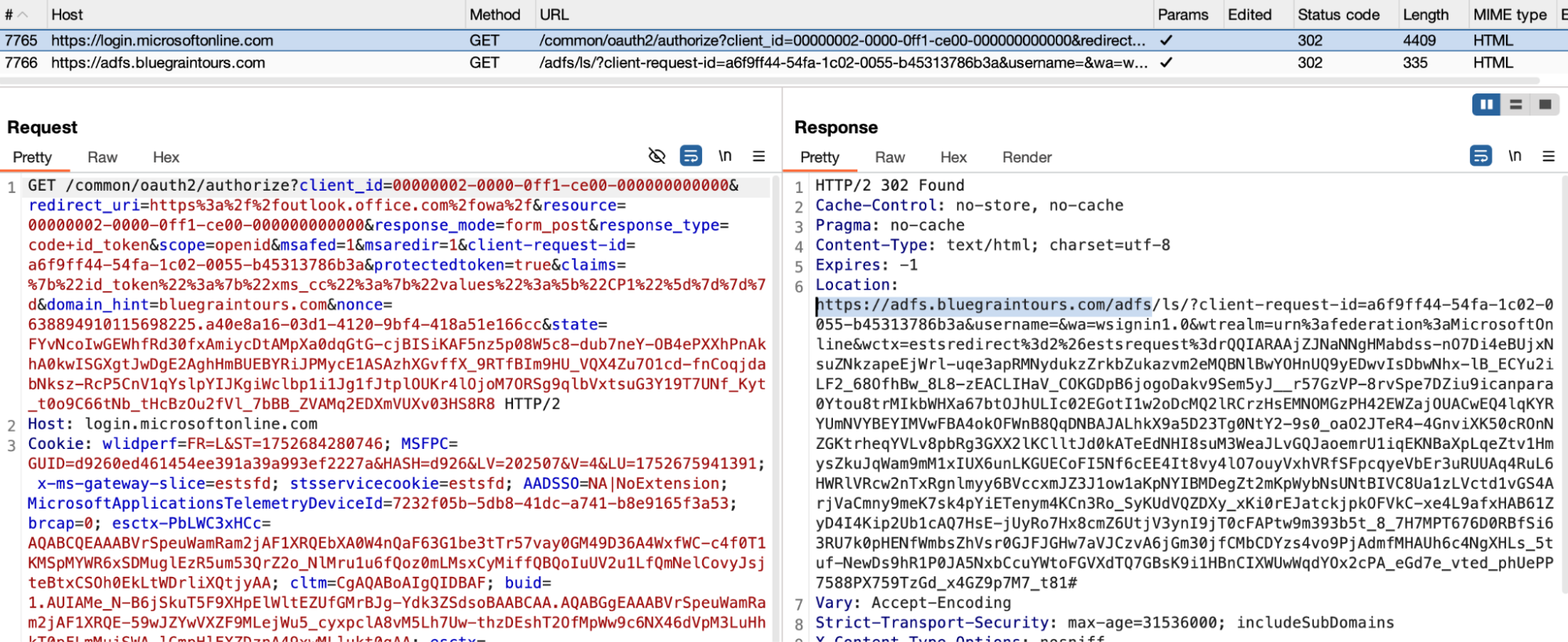

It turns out the attacker had set up a custom Microsoft tenant with Active Directory Federation Services (ADFS) configured. If you’re not familiar, ADFS is an SSO solution that is often used to connect on-premises Active Directory with cloud services like Microsoft 365 or Azure Active Directory. This means Microsoft will perform the redirect to the custom malicious domain.

This is strikingly similar to SAMLjacking, a technique I’ve blogged about previously which allows you to change the identity provider domain that an application’s users authenticate through. Attackers can change this link to their phishing page that proxies the legitimate site to phish users through legitimate sign-in links — so I guess that makes this ADFSjacking?

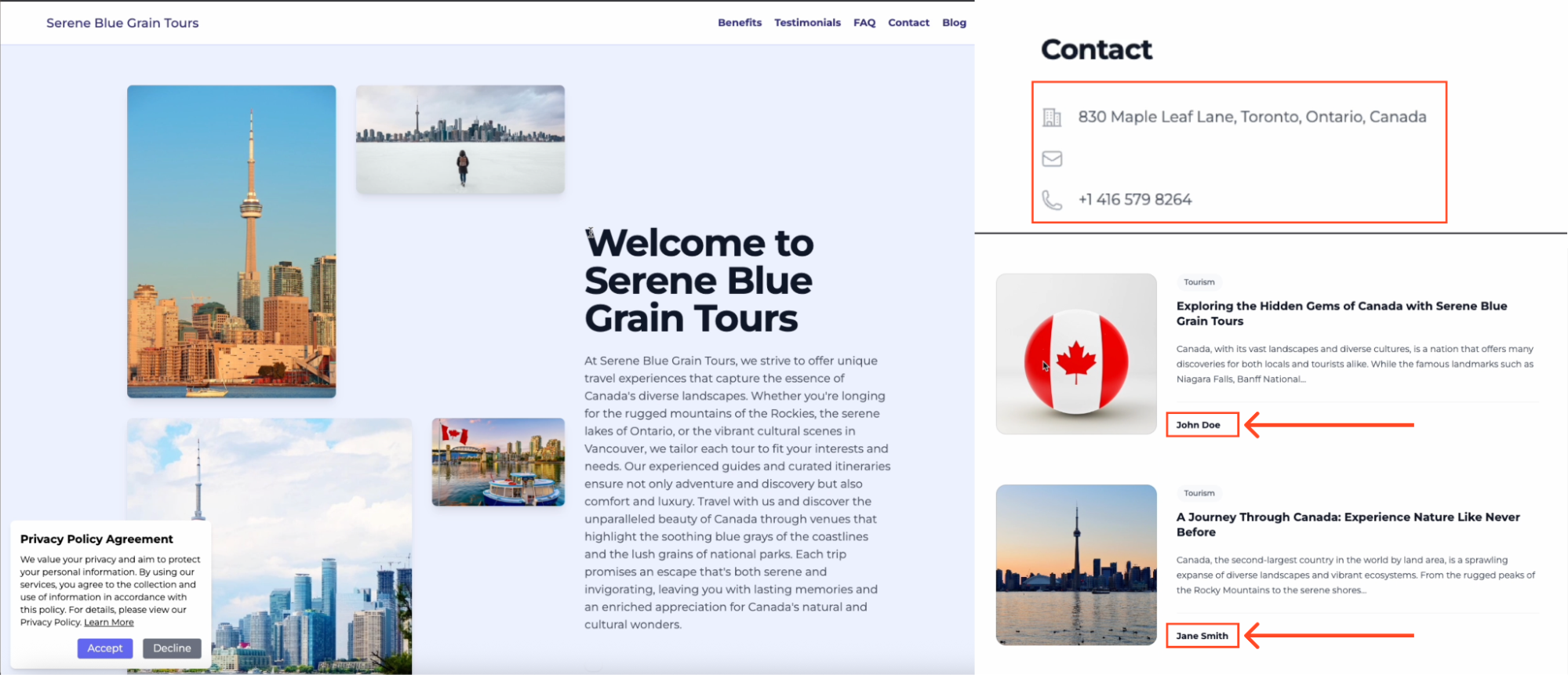

I had initially assumed that bluegraintours was a legitimate website that had been compromised by the attacker and used as a redirect, which is pretty common behavior for threat groups. However, it turns out that it’s actually a fake website that the attackers have probably vibe-coded.

It’s worth noting that this isn’t something that the phishing victim would see as part of the attack — it’s purely used as an invisible redirect. This is most likely to be an attempt to mask the nature of the domain for domain categorization purposes, which is typical for proxy-based solutions to prevent users from browsing to unapproved things — this way, automated scanners will classify it as a travel blog.

Conditional loading interrupted the page analysis

While the user was taken to the phishing page at the end of the chain, conditional loading restrictions prevented us from recreating the full attack flow when loading the initial link clicked by the user. This happens when certain conditions of the page load aren’t met. Because the kit decides I’m not a valid target, I’m redirected back to office.com. However, we were able to skip ahead and bypass the conditional loading to access the phishing server directly.

Key takeaways

While this isn’t a vulnerability per se, the ability for attackers to add their own Microsoft ADFS server to host their phishing page and have Microsoft redirect to it is a concerning development that will make URL-based detections even more challenging than they already are. Hosting phishing links on trusted third-party websites is a highly effective way of both bypassing URL-based detections and implementing layers of obfuscation in their phishing delivery chain that can break automated analysis tools.

This is basically the equivalent to Outlook.com having an open redirect vulnerability, which would be a huge deal in the eyes of most security practitioners. In practice, it’s a little harder for the average attacker to make use of this, but anyone that is willing to create a Microsoft tenant and set up ADFS could create similar phishing infrastructure — which only requires passing a credit card check.

The other notable component to this attack is the use of malvertising as the lure delivery channel. This is a trend we spotted recently with Scattered Spider’s use of Onfido-based malvertising lures. Malvertising is a great way for attackers to sidestep phishing controls placed at the email layer (where the majority are) and, as in this case, can create a highly-convincing and difficult-to-spot phishing scenario.

Detection recommendations

There are a couple of tool-agnostic hardening options that can used to limit exposure to the specifics of this attack:

Monitoring for ADFS redirects in proxy logs that could be malicious, i.e. login.microsoftonline.com redirecting to another domain with /adfs/ls/ in the path. Many organizations do not use ADFS, while those that do should be able to filter legitimate ones to their legitimate domain relatively easily.

Monitoring for Google redirects to office.com with Google ad parameters for more specific detection of malvertising + ADFS hijacking as in this example.

Deploying ad blockers to all of your browsers to stop malvertising attacks — though this only serves to tackle one of the several possible delivery vectors, such as links delivered using legitimate third-party services, social media, instant messenger, or email attachment. (This is one of the limitations of focusing on specific delivery mechanisms — attackers have more to choose from than ever before. It’s not just an email problem).

Learn more about Push

Push doesn’t detect the redirect tricks, or relies on outdated domain TI feeds. It doesn’t matter what delivery channel or camouflage methods are used, Push detects and blocks attacks by identifying the attack in real time, as the user loads the page in their web browser.

Push’s browser-based security platform provides comprehensive identity attack detection and response capabilities against techniques like AiTM phishing, credential stuffing, password spraying, and session hijacking using stolen session tokens.

You can also use Push to find and fix identity vulnerabilities across every app that your employees use, including ghost logins; SSO coverage gaps; MFA gaps; weak, breached and reused passwords; risky OAuth integrations; and more.

If you want to learn more about how Push helps you to detect and defeat common identity attack techniques, request a demo.