How ghost logins – where an application user account can have multiple simultaneous logins using different sign-in methods – can be leveraged by attackers throughout the different stages of a cyber attack.

How ghost logins – where an application user account can have multiple simultaneous logins using different sign-in methods – can be leveraged by attackers throughout the different stages of a cyber attack.

Identity attacks like phishing, credential stuffing, and session hijacking are now the leading cause of cyber security breaches, as attackers shift their attention to the sprawl of third-party applications and services that has become the backbone of business IT.

The attacker’s goal in these attacks is account takeover: logging into a user account to access your company app tenant. From there, the attacker can usually achieve all of their objectives from inside the compromised app, usually involving dumping sensitive data with which to hold the company to ransom, or selling the data on underground criminal marketplaces.

These attack techniques have been commonplace for over a decade — but the shift in attack context away from attacking endpoints (user devices and servers) to cloud services is seeing something of an identity attack renaissance.

Ghost logins are one of the leading factors in successful credential stuffing attacks driving account takeover.

Ghost logins 101

Simply put, ghost logins are often-forgotten alternative login methods that are tricky for security teams to manage and secure — because they don’t know about them. Because of this, they’re likely to possess weak configurations that make them susceptible to account takeover attacks.

We found that ghost logins are present in ~10% of the accounts per organization.

Why do ghost logins exist?

Identity management used to be something that was centrally contained and managed using an enterprise identity service like Active Directory. Most users probably only had one or two identities that you really cared about: the one they used to log into their company laptop and domain, and maybe also to log into a VPN.

Now, there are 200+ business apps in use per company, creating 1000s of sprawled identities across an ecosystem of business apps and services accessed over the internet.

Most businesses have tried to solve this problem with single sign on (SSO). The logic being that if you can use a single set of credentials (and therefore, a single identity) to access all of your business apps, and then secure those credentials with MFA, then this problem goes away. However…

SSO expectations versus reality

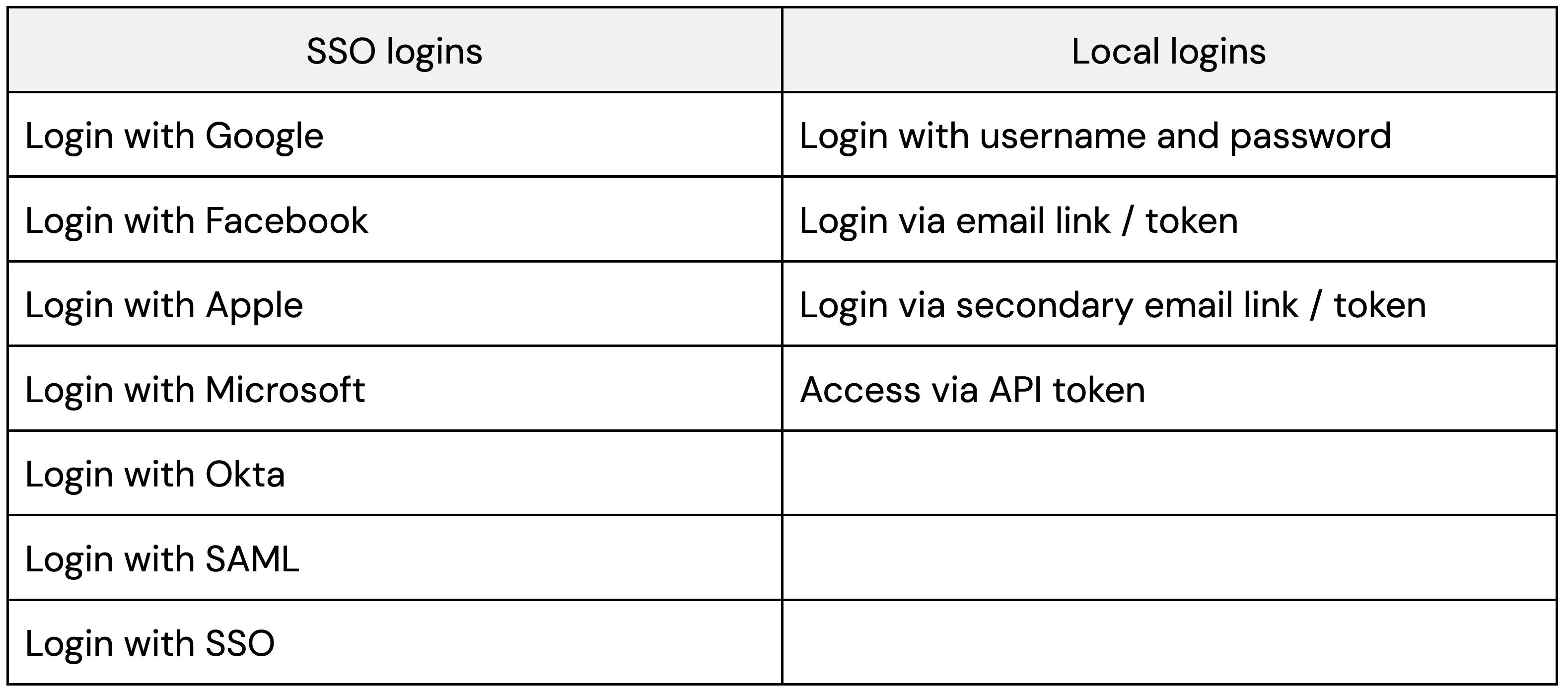

Unfortunately, the reality of SSO implementation is flawed. Most apps accept multiple login methods that can be configured — and used — simultaneously (yes, most apps don’t have proper session controls).

This is made worse by the fact that:

Most apps can't be locked down to restrict which login methods are accepted.

Users often self-adopt apps, and default to a username and password (and typically miss out MFA).

SSO isn’t always possible if you aren’t using a supported IdP — and only one in three apps support SAML, the preferred enterprise-grade protocol.

Even where SSO is possible, configuring an app for SSO doesn't automatically delete any legacy local logins.

Inevitably, this means that there are many situations in which users will create local accounts — typically with a username and password, and without MFA. This is how ghost logins are born.

How are ghost logins created?

Ghost logins can be created in the following ways:

A user self-adopts an app, setting up an account with a local username and password. The app is later adopted companywide and brought under SSO. This creates an additional SSO login method, likely as the default, but the local login will continue to exist unless explicitly disabled or deleted.

Secondary/backup login methods can often be added later in the app settings after logging in. This includes things like setting up a secondary email to send a login link to, or setting up API access to remove the need to authenticate altogether.

So, ghost logins are very easily introduced through the normal course of app adoption and use by employees.

Why do ghost logins pose a risk?

Ghost logins pose a risk for a number of reasons, as they:

Typically have less secure configurations than your preferred login method – and may be missing key controls like MFA.

Are effectively shadow logins – IT/security don’t know about them, and if using an IdP as your primary identity security interface, they won’t necessarily be visible without taking a deeper look at individual apps.

Can be used simultaneously with SSO – so you can have an unrestricted number of concurrent sessions with SSO and non SSO logins active at the same time, without the user being kicked out of the previous session.

Ghost logins provide opportunities for attackers to bypass security controls for initial access and persistence in an application (which we’ll come onto in more detail later). They also provide an opportunity for malicious insiders, e.g. a disgruntled employee, to access systems even after SSO access is revoked. If the security team relies on IdP logs to audit app logins, these accounts can go undetected.

To be able to identify them, you’d need to log into the app admin dashboard. But depending on how the app was adopted, you (as a security admin) may not even be an app-level admin — it’s not unusual for individual teams to administer their own apps. And even if you do have access, it’s not always easy (or possible) to gather this level of information about user account configuration.

It’s very easy to see how these vulnerable login methods can be overlooked by security teams – let’s look at how they can be identified and exploited by attackers.

How can ghost logins be exploited by attackers?

Let’s take an example scenario: You’re using an IdP solution like Okta or Microsoft/Entra with SAML SSO as the default login method for your core business apps. Via your IdP you require MFA when authenticating to your IdP apps page, and also potentially when signing into an individual connected app.

However, you only recently introduced your IdP solution, and your users previously accessed this app with a local username and password. Although you asked your users to configure MFA in the app itself, not all of them did. And when you deployed your IdP solution, you didn’t manually unset all the local password-based logins for the apps you connected to it.

Unknown to you, there are now hundreds of local accounts for core business apps which lack MFA.

There are two main scenarios in which ghost logins can be utilized by an attacker:

To bypass robustly configured login methods such as SSO to compromise an app identity during the initial access phase of an attack.

To create additional login methods for an already compromised account to ensure persistent access – even if the original compromised login method is revoked or disabled. This could be either the result of compromising an identity belonging to a specific app, or having previously compromised an IdP account (e.g. Okta).

Let's look at these use cases in more detail.

Ghost logins for initial access

Arguably the most dangerous use case for ghost logins is to conduct credential attacks against accounts using a username and password. Logins with a weak or guessable password, or a reused password that has appeared in a public data breach dump, are primed for account takeover.

The cyber crime ecosystem is leaning toward the theft, sale, and use of stolen credentials (not just emails and passwords, but session tokens too).

There are 600 million identity attacks per day, with 99% involving passwords (Microsoft).

Over 1000 credentials are posted online per day, per marketplace with an average sale price of $10, and 65% posted less than one day after being collected (Verizon).

One million new stealer logs are distributed every month, with an estimated 3-5% containing credentials and session cookies to corporate IT environments (Flare).

So, it’s easier than ever for attackers to gather breached credentials and weaponize them at scale.

Realistically, any username and password combination for addresses belonging to a specific organization/domain can be attempted on any app. Breached credential data will often provide a strong indicator of other apps also in use for that organization. And for apps with a custom tenant URL (that cannot be easily guessed) data dumps often helpfully include the URLs for those login pages, too.

The risk posed by the massive amounts of leaked credentials available is heightened because:

Many employees reuse passwords, with ~9% of all accounts using a breached, weak, or reused password. This isn’t just for low-risk apps either, and includes the reuse of highly sensitive IdP creds.

Organizations don’t typically rotate or enforce changes to SaaS app passwords in the same way they might for company account/device login connected to Active Directory.

Ghost logins aren’t limited to just username and password either. For example, a breached social account such as Facebook or Google can result in a broader compromise if those accounts have been connected to any corporate apps.

So, exploiting ghost logins can be a highly effective method for attackers to gain initial access to a user account from which to launch further attacks.

Ghost logins for persistence and defense evasion

Now, we’ll take a look at how attackers can leverage ghost logins as part of the later stages of an attack, having already established an initial foothold via account compromise.

If an organization has a reasonable level of security monitoring in-place (depending on log availability from the particular app vendor), or a victim receives a notification about an unusual login (e.g. from a new device or unusual IP) then access to an account can be short-lived. However, ghost logins can provide attackers with the tools to maintain persistent access to a compromised account, even if the initial compromised login method is disabled or revoked.

For example, if a social login is used to access an account, an adversary may be able to configure a separate username/password login, or even (though much less commonly) connect a second social account that the adversary controls. This allows the adversary to maintain persistent access to the user account even in the event of password changes or MFA changes. The attack will go unnoticed if the victim organization relies on SSO logs for auditing access to SaaS applications because the attack bypasses SSO, as the login remains local to the SaaS app or, in the case of an OIDC SSO login, the adversary’s own social account.

Another quirk is that it’s common for ordinary users to become app-level admins when an app is self-adopted by an individual or team. If an attacker is able to gain control of such an account, it can then be used to target other users without needing to deliver phishing links by hijacking SAML-based authentication. In this scenario, users attempting to sign in using SAML SSO are directed it to an attacker-controlled tenant in a watering hole attack (also known as SAMLjacking, which you can read more about in another blog post).

If you're curious as to how an attacker might be able to compromise an IdP account such as Okta, you should check out our blog post on AitM and BitM phishing techniques.

Case study: Snowflake

The recent attacks on 165 Snowflake customers, resulting in hundreds of millions of breached customer records, were the product of a credential stuffing campaign using stolen credentials from infostealer infections dating back to 2020.

The industry response to Snowflake was typical: check whether Snowflake has been set up for SSO, and if so, job done — we’re protected by MFA.

The reality was that MFA was not — and could not — be centrally enforced for username and password accounts. Even if MFA was applied at the IdP level for SSO logins, it was not enforced for local username and password logins. It needed to be opted-into by the user.

This meant the most logical thing to do was to disable local accounts. But because Snowflake is essentially a cloud-hosted SQL database, there was no easy-to-use GUI to access local account config data. Once you’d managed to get an admin account with the right permissions, you needed to run various commands to find and unset the accounts. But if you didn’t have the exact type of admin account, misleading results would be returned — and even after you had fixed the vulnerability it took hours to update the database.

This meant that organizations were exposed to these attacks for a prolonged period, and were left uncertain as to whether they had addressed the vulnerabilities or not.

Using Push to find and fix ghost logins across your app inventory

Finding and fixing ghost logins is a challenge for most organizations. Since you can’t rely on the view provided by your IdP, you need to:

Discover the apps in use across your organization

Get admin rights, audit each app, and unset any local credentials (enforcing MFA at the app-level too if you can, for good measure)

Configure the app to prevent local accounts being created (again, if possible)

Not only is this a sisyphean task with continually moving goalposts, but depending on which apps you use, and how they’ve been designed, it may not be possible to remediate every instance of ghost logins. For that reason, it’s important to also invest in your identity threat detection and response capabilities — for when, not if, an account takeover attempt occurs.

Push helps organizations to defend against ghost logins and other identity threats with a defense-in-depth approach: Using a browser-based agent to generate visibility of all logins (not just via IdP logs) while also detecting, intercepting, and shutting down account takeover attempts via phishing, credential stuffing, and session hijacking. Learn more here.

And if you'd like to learn more about ghost logins and other identity attack techniques, check out the SaaS attack matrix on GitHub.